Bulgaria, a small Balkan nation of about seven million people, has struggled to form a stable government for the past two years. After five inconclusive parliamentary elections since 2021, the country remains in a political deadlock, with no clear majority or coalition in sight. The main reason for this impasse is the personal animosity between the two largest blocs: the center-right GERB party of former prime minister Boyko Borissov and the pro-Western reformist bloc led by We Continue the Change (PP) and Democratic Bulgaria (DB).

But there is another political force that has been gaining ground in this turbulent context: the Revival party (Vazrazhdane), a far-right and ultranationalist group that advocates for closer ties with Russia and opposes Bulgaria’s membership in the European Union and NATO. The party, founded in 2014 by Kostadin Kostadinov, a former member of another nationalist party, IMRO-BNM, has attracted voters by rehashing Kremlin propaganda and urging delay to the introduction of the euro in the run-up to the election. The party has also promoted conspiracy theories regarding COVID-19 and had strong reservations regarding COVID-19 vaccines.

In the latest snap election held on April 2, 2023, Revival came third with 14.4% of the votes, up from 4.86% in November 2021. The party now holds 27 seats in the 240-member Parliament, making it a potential kingmaker in coalition talks. However, both GERB and PP/DB have ruled out any cooperation with Revival, citing its anti-democratic and pro-Russian positions.

What does Revival stand for, and why does it appeal to some Bulgarian voters? According to its website, Revival is the country’s only patriotic party, and its main goals are to restore Bulgaria’s sovereignty, dignity, and prosperity. The party claims that Bulgaria has been exploited and humiliated by the EU and NATO, which have imposed harmful policies and sanctions on the country, and it has called for votes on Bulgarian’s membership in both institutions. The party also accuses the West of supporting Ukraine’s “fascist” regime and provoking a war with Russia, which it considers a “brotherly” nation and a strategic partner. Although many experts dismiss this rhetoric as campaign posturing, they warn that the party may be acting in the interests of the Kremlin.

“In my opinion, hidden behind these positions of Revival is an agenda to set as large a part of Bulgarian society as possible against the EU, to separate Bulgaria from a united Europe and the free world, to turn us into a peripheral authoritarian state of the repressive Russian regime,” Hristo Hristev, a professor of EU law at Sofia University.

Revival’s pro-Russian stance is not surprising, given Bulgaria’s historical and cultural ties with Russia. Bulgaria was liberated from Ottoman rule by Russia in 1878 and remained under Soviet influence until 1989. Many Bulgarians still feel gratitude and affinity towards Russia, especially among older generations. Moreover, Bulgaria depends on Russia for most of its energy supplies and has significant trade and tourism links with its northern neighbor.

A May 2022 Bulgarian media report titled “Is Bulgaria the weak link in Europe’s fight against Russian disinformation” said pro-Russian propaganda has been “flooding the country for years:.”

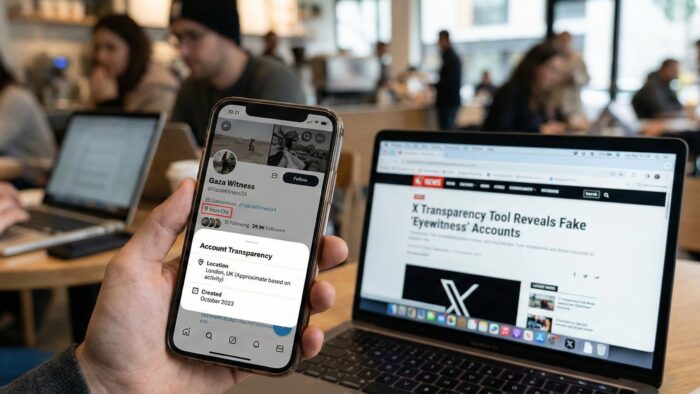

The Center for the Study of Democracy in Sofia has found that Russia’s use of social media has helped to amplify its views and influence in Bulgaria following the invasion. According to Goran Georgiev, the Center’s representative, Russia’s social media presence in Bulgaria is particularly strong, with more interactions than all of its rivals combined. The social media presence of Russia’s embassy in Sofia alone reached almost 2 million interactions on Facebook in 2022. However, Georgiev also noted that only 30 percent of Bulgarians think of Russia as a threat, a significant increase from the 5 percent before the war.

However, not all Bulgarians share Revival’s admiration for Putin and his policies. According to polling, many younger and more educated Bulgarians see Russia as a threat to their country’s security and democracy and support Bulgaria’s integration into the EU and NATO. They also resent Revival’s ultranationalist rhetoric, which often targets ethnic minorities such as Turks and Roma, as well as sexual minorities and feminists. Meanwhile, people over 60 remain the nucleus of the support for Russian policy.

The November 2022 decision by the Bulgarian Parliament to approve sending military aid to Ukraine points to the divisions between the Bulgaria parliament on the issue and the role of the pro-Russian parties.

The rise of Revival reflects the deep divisions and frustrations that plague Bulgarian society. On the one hand, there is a desire for change and reform, as evidenced by the anti-corruption protests that erupted in 2020 and 2021 against Borissov’s government. On the other hand, there is a nostalgia for stability and order, as well as a distrust of Western institutions and values. Revival taps into both sentiments, offering a populist and nationalist alternative to the mainstream parties.

Whether Revival will be able to translate its electoral success into political influence remains to be seen. The party faces strong opposition from both sides of the political spectrum, as well as from civil society groups and media outlets that denounce its extremist views. Moreover, the party may face internal challenges, as some of its members have been accused of corruption or links with organized crime.

References:

https://www.global-influence-ops.com/pro-russian-political-parties-in-bulgaria-trouble-ahead/

https://www.ft.com/content/88603542–7f82-4dfd-a4bf-bfd023f96451

https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/central-right-bloc-gerb-sds-wins-bulgarian-snap-elections/2862121

https://www.dw.com/en/nato-or-moscow-bulgaria-torn-between-russia-and-the-west/a‑61036527